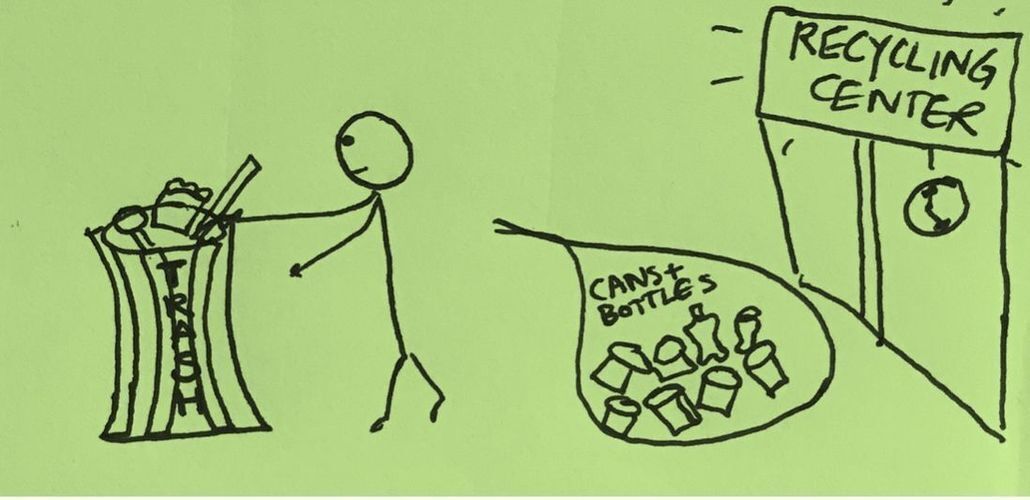

I Had to 'Unlearn' Medicine to Treat Survivors

Sometimes people ask what it's like to provide care for PurpLE patients -- survivors of human trafficking, domestic violence, and other forms of gender-based violence. I tell them I've had to "unlearn" how I practice medicine. And then I show them my drawings to explain why. Here are a few examples:

Food

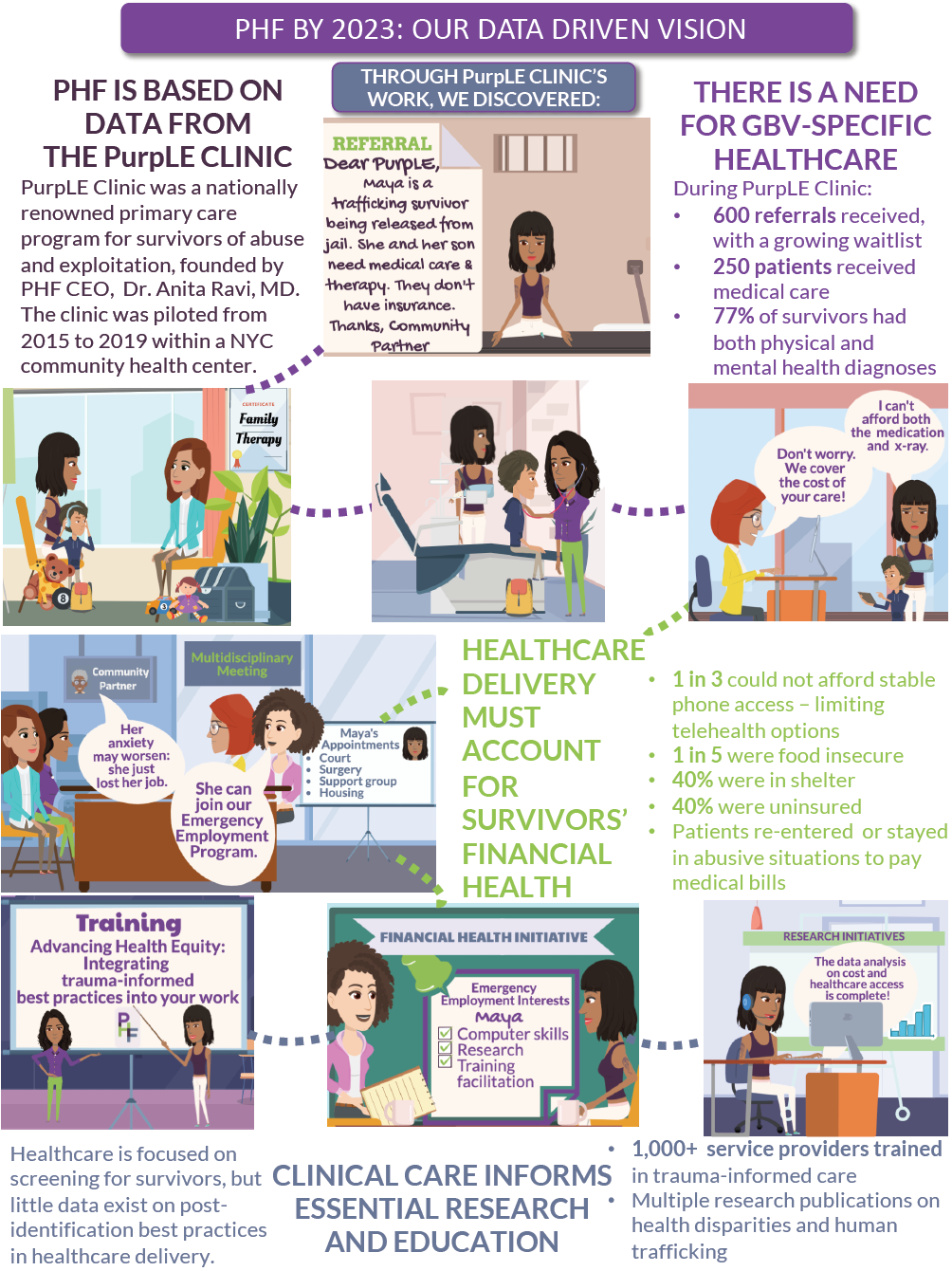

PurpLE patients sometimes seek care to address ongoing pain related to injuries sustained while trafficked or experiencing partner violence. And when I would prescribe an anti-inflammatory medication to help with their symptoms, I didn't think twice about saying, "Make sure you take this with food" -- until I was met with a blank stare. Because ten minutes earlier, a patient may have shared that they were feeling stressed out about not having income and relying on a friend who worked in a restaurant to bring leftovers to eat; sometimes there were none. I realized that what I was actually communicating with my prescription instructions was that I had been hearing but not listening. I needed to unlearn the idea that common medical advice has universal applicability, and instead learn that some prescriptions need their own treatment -- such as assisting with food access -- to help a patient.

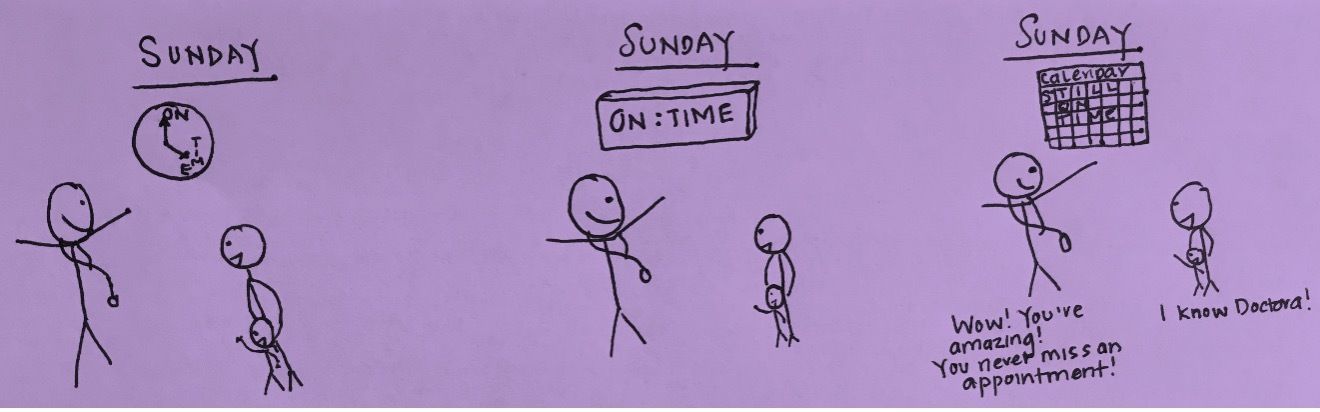

My assumptions regarding food have been tested in other ways, too. Patients sometimes call to say they are running late for many reasons -- sometimes because they want to get food because they haven't eaten...in a few days. This was not an uncommon reason for patients to be delayed, so I said I completely understood, envisioning the following scenario:

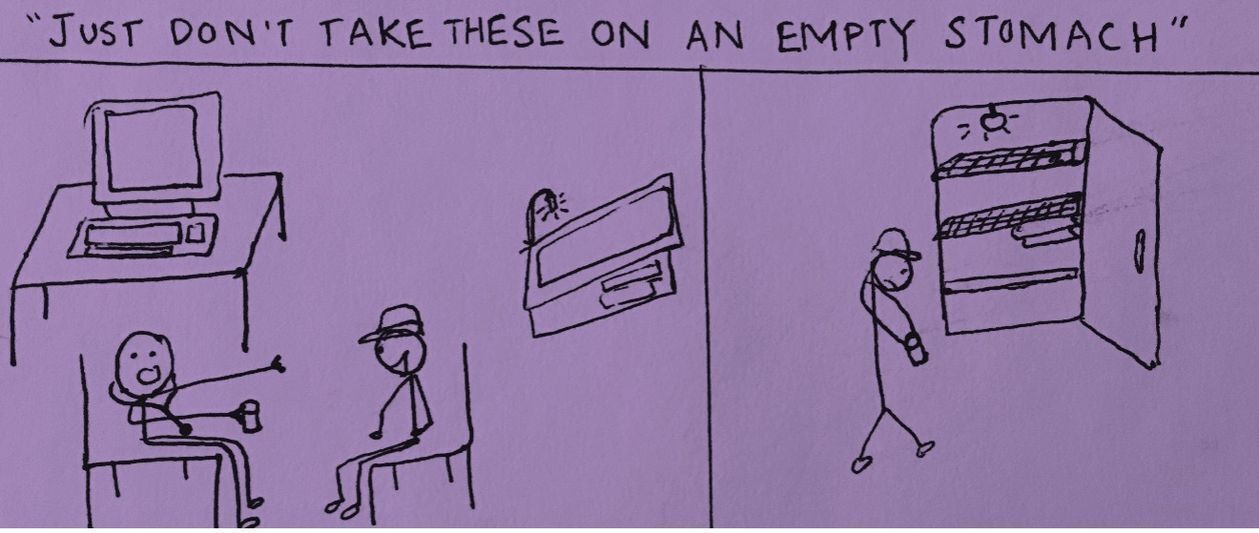

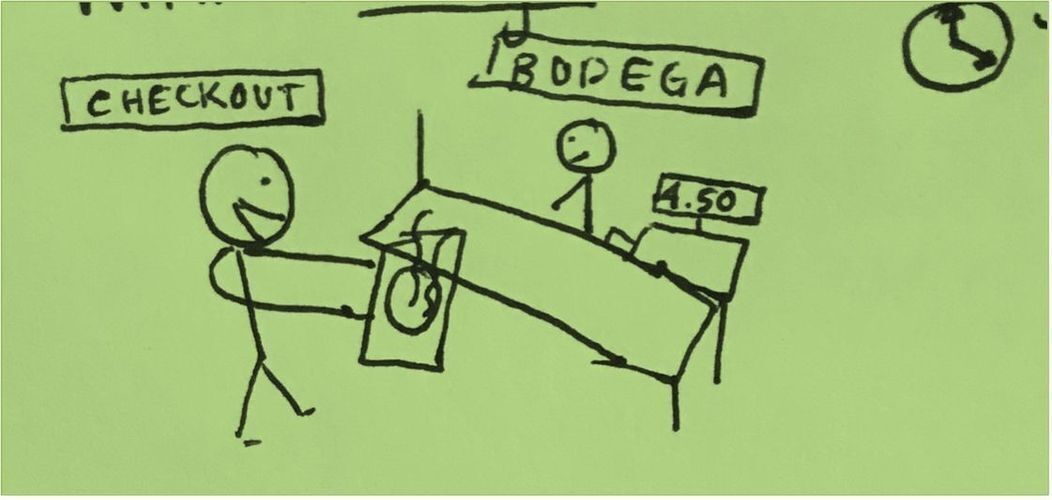

But one time, when a patient came in delayed because she needed to get food, I asked what she had eaten, and she responded, "Nothing," because she had only "collected $3.83 worth." And then I realized...she was paying for food by collecting cans and bottles on the street to recycle, and she had come up short.

Hunger is frequently addressed during PurpLE appointments.

"When was the last time you ate?" is something physicians ask when we order labs that require fasting. I've unlearned the purpose of this question. Having implemented a way to provide point-of-care access to food, I now ask "When was the last time you ate?" to ensure no one leaves the clinic hungry.

Transportation

As I mentioned, patients at PurpLE often come in later than scheduled for many reasons. Life is unpredictable. Some undocumented patients rely on informal networks for jobs and may find out the night before that a hair-braiding, construction or housekeeping job has become available. Some patients, however, always make it on time and never miss an appointment.

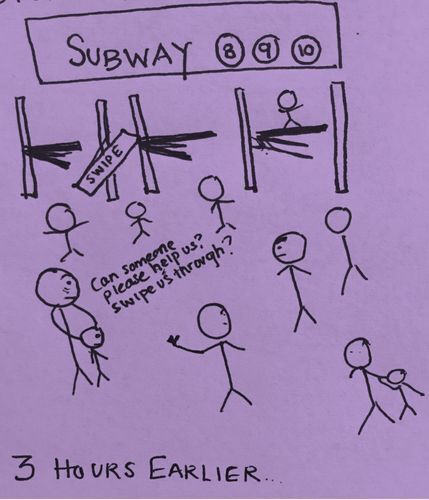

So I started asking them how they do it, and that's when I found out what was happening. One of my patients shared that before every visit, she and her child would leave their place several hours early because they could not afford subway fare and relied on strangers to "swipe" them through. They did this to attend every appointment and they did it again after leaving the clinic.

Other patients said they had to decide between eating a meal or paying subway fare -- making appointment days particularly difficult. In New York City, where issues such as turnstile-hopping can result in arrest, it was troubling that attending appointments could be a link in the cycle of poverty and incarceration. To address this, I needed to unlearn that on-time appointments were a measure of success in health care delivery, and our team implemented a system that made subway cards available to patients.

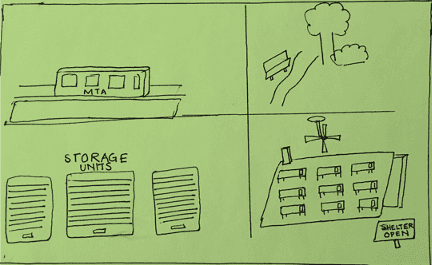

Housing

I've also learned that sometimes the subway is not just transportation -- it may also be housing.

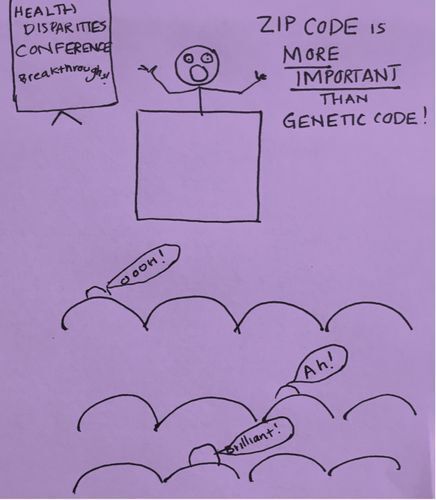

Initially, I found solace in headlines from population health research that declared ZIP codes have more influence on health than genetic codes because this signaled an important shift in the health care system's understanding of the role of social determinants of health.

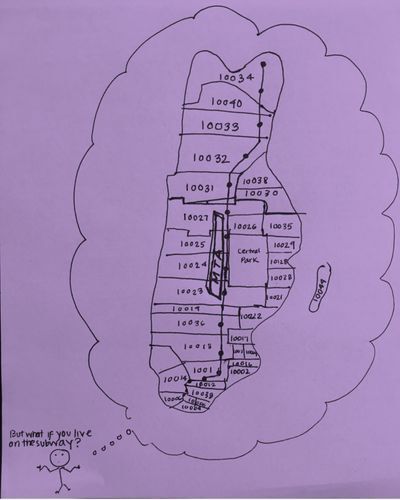

But then I started to wonder whether PurpLE patients were accounted for in these findings. Patients in domestic violence shelters live in confidential locations and have only post office boxes. Their ZIP code may be unrelated to where they live. Patients staying with friends or couch-surfing to escape an abuser have different ZIP codes every day. And patients living on the subway don't have just one ZIP code. They have at least 10 in one day. In our clinic, I have unlearned that a ZIP code tells me where someone lives. It only tells me where they receive their mail.

PurpLE has made me realize that highlighting the narratives of those whose vulnerable circumstances may be hidden at a population level is an essential form of advocacy. Recommendations rooted in lessons learned from direct patient care offer complementary insight to lessons learned from population health research. Both are necessary to ensure that key stakeholders, including policymakers and health system entrepreneurs, consider the breadth of people's circumstances when they create policy, allocate funding or design their next health care app.

These are some examples of unlearning the practice of medicine that I have found essential to being a family doctor. I know these lessons may be intuitive to some and largely inapplicable to others. But to students and residents embarking on their careers, I say this: I hope that you will routinely check your own reflexes to make sure that the advice you are taught to give is applicable to the patients you are expected to help. And I hope you have the freedom to question whether innovations in research and policy account for your patients' circumstances -- and the opportunity to design solutions that do.