Care of Homeless Patients Requires More Than Referrals

I used to think I knew how to manage any social issue my patients faced by clicking one magic box in their chart: "Refer to social work."

I have since learned that "clicking" is not the cure to managing social determinants of health in medicine. But I am worried that health care systems have not learned the same lesson.

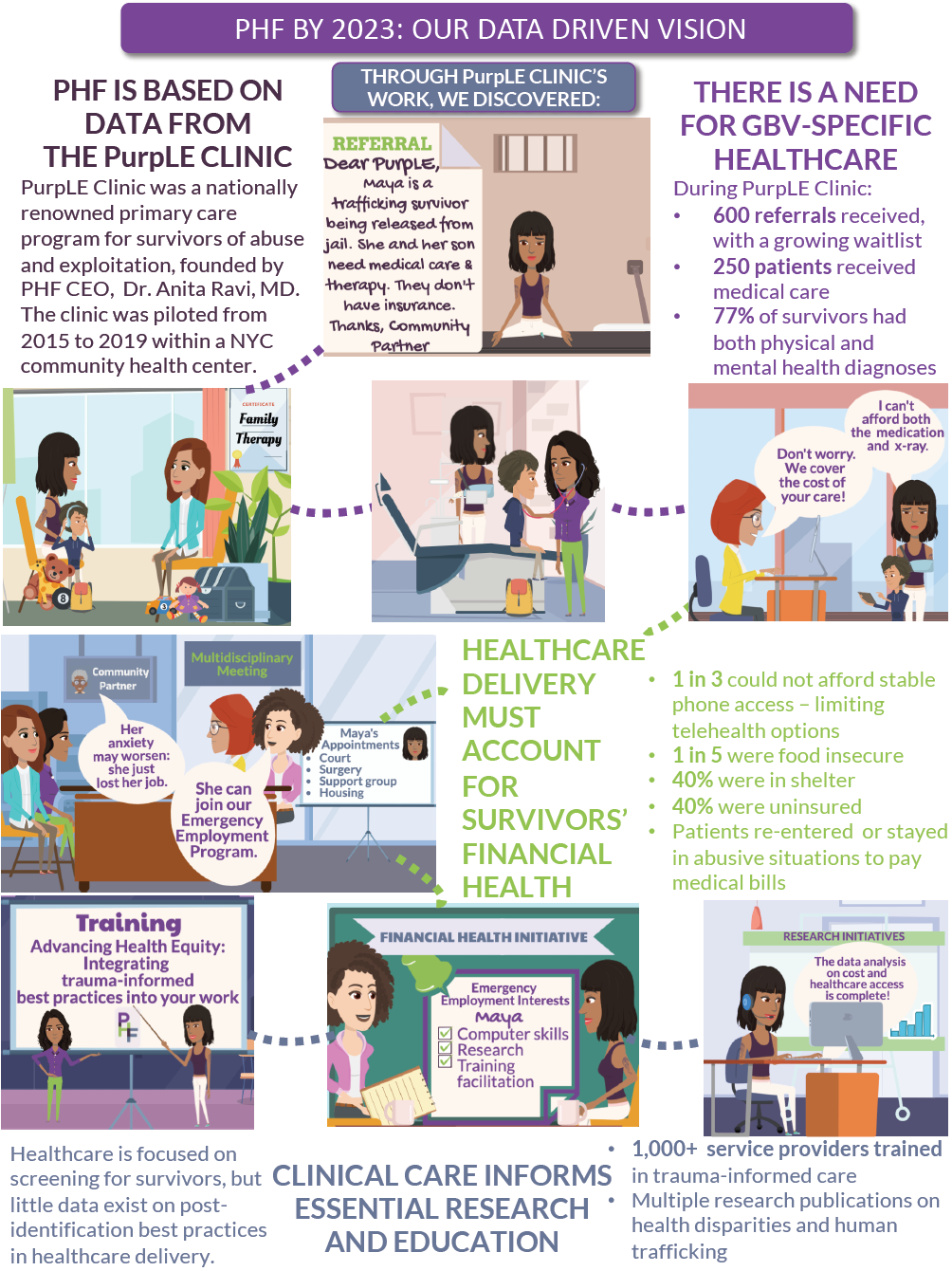

Defined as the conditions under which people are born, grow, live, work and age -- such as housing, food, education, and employment -- "SDOH" has become an exciting buzzword in health care. It is born from the belief that investing in SDOH will result in improved health outcomes and cost savings. But somehow, embracing this belief has manifested as a hyperfocus on efficient SDOH screening tools, with minimum physician involvement beyond placing a referral to connect patients with social services.

My experience while designing and running a primary care clinic for survivors of domestic violence and human trafficking has taught me that addressing SDOH requires a deeper investment. It requires integrating them into medical education, guidelines and systems.

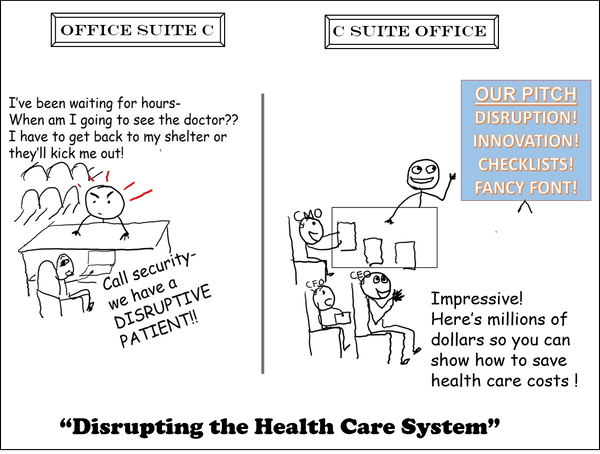

Take housing, for example. When patients hand back an SDOH screening tool with the box checked for "I do not have housing," I find myself awash in a sea empty of evidence-based recommendations for working with patients (particularly women and youth) with unstable housing. To stay afloat, I piece together "best practices" from patterns I see in interacting with patients and creating "micro-innovations" to solve unexpected but common problems. My experience has made me wary of watching hospital CEOs spend millions of dollars on consultants who are supposed to "disruptively innovate" the health care system, while patients who are deemed problematic or "disruptive" in these same systems are the ones who have taught me the most about the bridge between SDOH and health care design.

Food

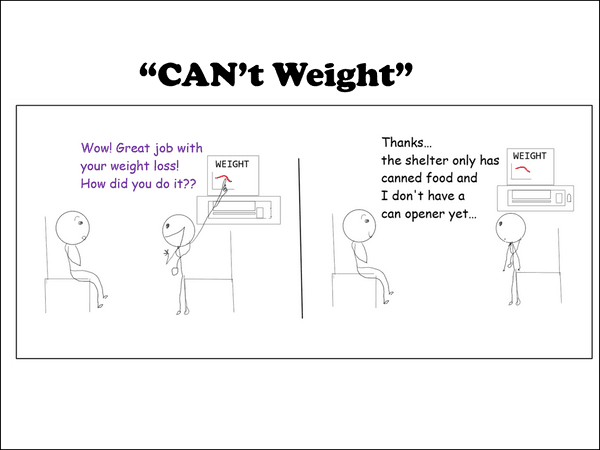

Doctors are trained to look for unintentional weight loss -- a possible sign of something concerning that warrants further investigation, such as cancer. But sometimes, it's a symptom of shelter placement.

I thought shelter access meant food access, especially in family and domestic violence shelters. I was wrong. Patients still go hungry. For patients who were refugees or awaiting asylum, the shelter diet is foreign to them or does not meet their cultural or religious needs (such as halal or kosher food), and they instead rely on sporadic community connections for meals. For patients with diabetes, high blood pressure or those hoping to address obesity, the choices of frozen and microwavable meals available in shelters don't match any of the items listed in their patient education handouts about making healthy nutritional choices.

So why is it that we are still even using these handouts in the age of innovation? Because the issue remains unsolved. I am often directed toward a multitude of phone apps, although I know my patients do not have routine phone access. And patients often cannot take the time off work, afford the transportation or arrange childcare to follow up on a list of recommended pantries or return to meet with the clinic's nutritionist for a more in-depth assessment.

Instead, we find ourselves waiting for an accessible nutrition tool that can provide culturally sensitive food options in the setting of dynamic shelter-based dietary options, limited access to kitchen equipment and financial struggles. For now, I am left printing out the generic "healthy choices" handout and checking the appropriate quality metric box in their chart, confirming to administrators that I addressed "obesity" with my patient. These moments manifest as moral injury for physicians at the front lines of care.

Bathrooms

Not feeling comfortable using bathrooms in shelters can impact a patient's health in a variety of ways. Sometimes conversations that begin with, "You're due for your colonoscopy," may end with, "Can we wait until I have my own bathroom? I don't want to be using that prep stuff or stool cards in the shared bathrooms." Concerns related to safety, facility cleanliness and resident drug use have led patients to avoid using shared shelter bathrooms, sometimes waiting until they get to work or school or even resorting to creating makeshift toilets in their room. The associated health implications will only be discussed in clinic if you know to ask about them.

But "waiting for stable housing," which can take years, is not an option I can choose on the electronic medical record to explain why patients choose to delay routine preventive care. These realities remain masked in population health data that is supposed to generate solutions for "underserved populations." Instead, I watch investment in "innovations" such as increasing outreach to these patients with phone calls and mailers to improve colon cancer screening rates when I know that outreach was never the problem. Bathrooms are. Health systems must have a deeper understanding of patient experiences in sectors outside of the health care system if they hope to invest in meaningful solutions.

Clothing

Although physicians consciously think of patients' access to clean clothes only rarely, the assumption that they have this access is embedded in many of the recommendations we make. Want to prevent a yeast infection? Wear clean cotton underwear and change out of wet clothes as soon as possible. Bed bugs? Launder your clothes in a prescriptive way. IUD insertion? Manage bleeding with pads instead of tampons for the first 24 hours. But universal adoption of these recommendations is problematic for some patients. Because shelter access does not necessarily mean clothing or laundry access, patients nervously let me know that they're not able to change their underwear every day because they can't afford laundry or, sometimes, they can't afford underwear at all.

Now, in preparation for a Pap smear, I replace instructions to remove "underwear" to "any clothing from the waist down." When discussing treatment plans, I ask whether recommendations related to accessing clean clothes are feasible. I was able to engineer these micro-innovations because my patients initiated these difficult conversations. A macro-innovation would be if health systems normalized teaching such practices, instead of patient shame serving as a prerequisite for teachable moments.

Sleep

Room-sharing in shelters can be tough, especially with strangers. Sometimes patients' nightmares related to post-traumatic stress disorder are so bad that their roommates complain, and fights ensue. And sometimes it's the other way around, where a roommate's behaviors can have a domino effect on the health of a patient. As one patient told me about her roommate: "She starts screaming in the middle of the night, and I end up going to work tired. I'm worried I'm going to lose my job."

Now I know to proactively ask about whether patients have an in-shelter roommate and how they're coping with related stress. Initiating these conversations communicates to patients that a seemingly nonmedical circumstance might be an obvious medical issue for which their doctor can be their advocate. The discussions lead to thinking beyond the traditional response to addressing "I can't sleep" with a sleep hygiene handout. That's because advice to "Make sure your bedroom is quiet, dark, relaxing and at a comfortable temperature" is loaded with an assumption of environmental control that is simply not applicable for patients facing housing insecurity. Instead, we may discuss starting medications that could help with PTSD symptoms or submitting a letter to the shelter manager that describes why moving to a single-occupancy room or a roommate change will contribute to improving the health issues my patient is tackling. Advocating for change in other sectors on the basis of a patient's health transform letters into valuable prescriptions.

Family Dynamics

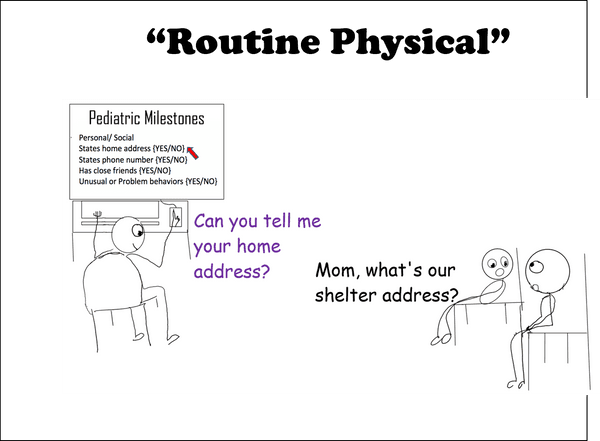

Throughout my medical education, I was trained (and tested on) what to ask to ensure children were developing normally: "How many blocks can they stack? Is toilet training on track? Can you recite your address and phone number?" But clinic painfully taught me that routine physicals for children were not designed to account for kids experiencing homelessness.

Well-child examinations used to surprise me when I would hear unexpected responses to routine questions. Patients have told me that they don't want other kids to find out they were in a shelter because they had seen homeless classmates bullied for being poor or smelling bad. Some lament that they can never host sleepovers like other kids do, or they talk about the difficulty joining sports teams because they have to change schools every three months, moving from shelter to shelter.

When the visit transitions to the parent, mothers -- particularly those in domestic violence situations -- share tremendous feelings of guilt for uprooting their children from stable housing and entering the family shelter system. Self-blame is also abundant when they bring their child in for health issues related to the housing conditions of the shelter: burns from uncovered heaters, bug bites due to roach infestations, regression in toilet training, and on and on. The specter of court systems also looms ever-present for these families because poor shelter conditions are sometimes weaponized during custody hearings or when a hospital admission for a mother with major depression can lead to loss of both the custody of her children and their spot in a family shelter.

I hope sharing these experiences can help doctors-in-training better prepare to care for families in shelter than the tests we take to get us here.

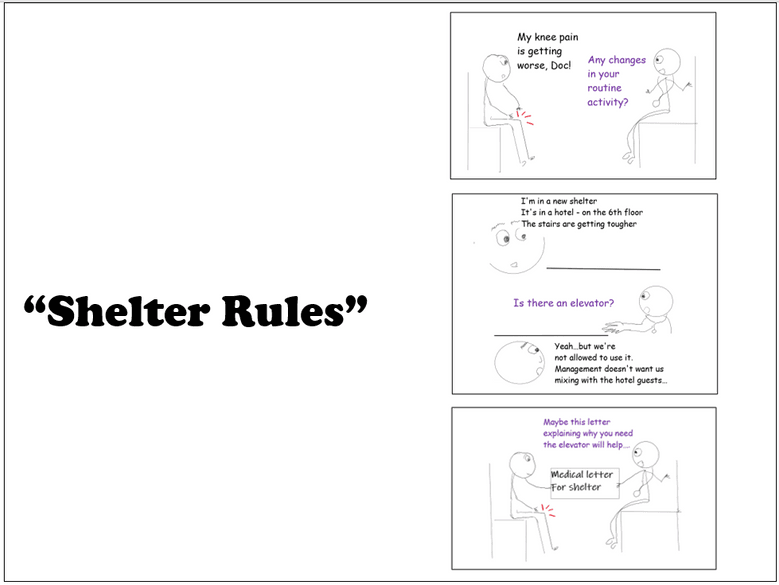

Shelter Rules

Health systems must understand the culture of shelters to create administrative protocols sensitive to patients in these situations. Some shelters require that patients vacate the space during the day, only allowing them overnight accommodations. The impact of this rule is that whenever I walk into the clinic room, patients frequently apologize for charging their phone. For some, it is their only access to an electrical outlet all day. As a result, it became clear that we needed to adopt a culture of care that communicated that we understand phone charging is a normal, routine health need. A dead phone has the potential to disrupt multiple SDOH, including missing calls from lawyers, schools, prospective employers and of course, doctor's offices calling with results. I now start every visit by asking patients if they would like to charge their phone during the appointment, and I let them know that we have every brand of phone charger available in the room in case they didn't bring one.

Even appointment scheduling can be optimized by recognizing that some shelters have curfew rules. I learned that patients could not afford to come in for a 5 p.m. appointment, have an unexpected one-hour wait if I had fallen behind in clinic, and make it back in time for their 7 p.m. curfew, so they often found themselves having to choose between medical care or losing their shelter spot. Consequently, I would find myself entering a diagnosis code of "left without being seen" and calling the patient to apologize and assist with appointment rescheduling. These patterns prompted changes in our own protocols: Staff now inquire about curfew restrictions when scheduling appointments, and they know to alert me if they are concerned that a patient might leave without being seen. These are just two examples of likely hundreds where health systems' investment in understanding shelter ecosystems could spark improvements in health care delivery redesign.

Alternatives to Shelter

In addition to rules and regulations, every shelter has a different set of amenities, programming expectations and staffing culture; some have a constant police presence, some have religious requirements, some mandate attendance for in-shelter programs, and some lord power over patients' mental health conditions in ways that mirror the power dynamics of prisoner and guard rather than a healing collaboration.

Why does this matter for doctors? This means that our "Refer to social work" does not always inoculate against homelessness, and we must be prepared to manage the outcomes accordingly.

Some of my patients have gone through the shelter system. A lot. And they'll never go back. Some run away from shelter, some would rather risk staying in an abusive relationship, and some may routinely trade sex for housing rather than jump through all of the inevitable administrative hoops, rules, regulations, and accompanying shame and stigma of the shelter process.

These realities reinforce that referral to social work is not the natural conclusion of a doctor's role working with patients experiencing homelessness. The health implications of not choosing shelter, such as increased risk for interpersonal violence, certain infections, jeopardized medication access and chaotic follow-up appointment scheduling, are realities that health care systems addressing SDOH must recognize.

Summary

The promised land of improved health and cost savings will forever be out of reach if the health care system remains resistant to understanding the complexities of the services to which we refer our patients. Housing is just one example of many social sectors, that, like health care, are bureaucratic, broken and under-resourced (just ask our social work colleagues). And yet, we pin our hopes on better patient outcomes every time we place a referral.

I believe the health care systems that will see a return on investment will have done so by encouraging disruption of the silos that perilously separate medical and social sectors and by engineering micro-innovations for the everyday ways in which SDOH present in a clinical room.