Last week, I joined the Immigration Justice Campaign's Dilley Pro Bono Project to assist asylum seekers at the South Texas Family Residential Center (STFRC). As a family doctor who does medical affidavits for people seeking asylum and runs a clinic for people who have experienced sexual violence and human rights related abuses, I have seen the long-term trajectories for mothers and children seeking asylum. I know it to be a traumatizing, years-long process during which time many experience homelessness, food insecurity and, unfortunately, even death.

Being in Dilley, Texas, showed me the beginning of my patients' journeys. For one week, our 18-person team of lawyers, students, translators and two physicians worked within the confines of a trailer to provide legal care for asylum-seeking mothers and their children. Although I'm still processing my experience, I wanted to share with you a few moments that stand out in my mind.

The Basics

Family detention holds mothers and their children who are fleeing persecution from their home country. To call these mothers and children "illegal" is legally incorrect. They are legally seeking asylum in the United States. The vast majority of the mothers in family detention are waiting a CFI- Credible Fear Interview. The credible fear standard means there is at least a 10 percent possibility that the person could establish eligibility for asylum. Legally, upon arrival they could have been released to their sponsor in the community (such as a sister or social worker at a community-based organization) with instructions to appear for their scheduled interview. But instead, we choose to detain them.

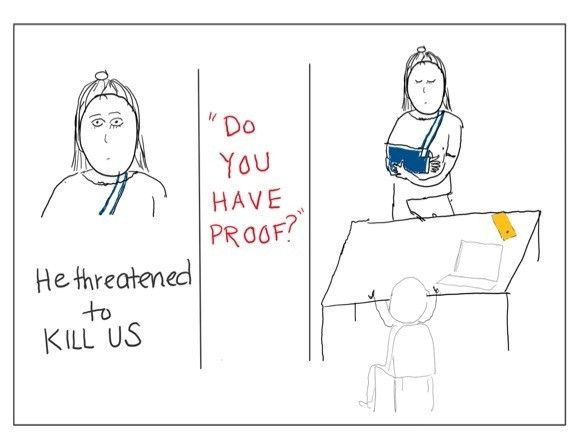

People are eligible for asylum in the United States if they suffered persecution or fear of persecution due to race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion. Most of the mothers being held in Dilley are from the "Northern Triangle" -- Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras, where gang violence and lethal domestic violence are rampant.

A "positive" result after their CFIs, means the mother can go on to apply for the years-long asylum process. A "negative" result means deportation. A main goal of our team was to assist clients with preparation for their CFIs.

The Moments

Located in Dilley, STFRC is the country's largest detention center, and is comprised of a compound of trailers: a mix of housing units, courts, medical and legal areas. STFRC holds only mothers and their children.

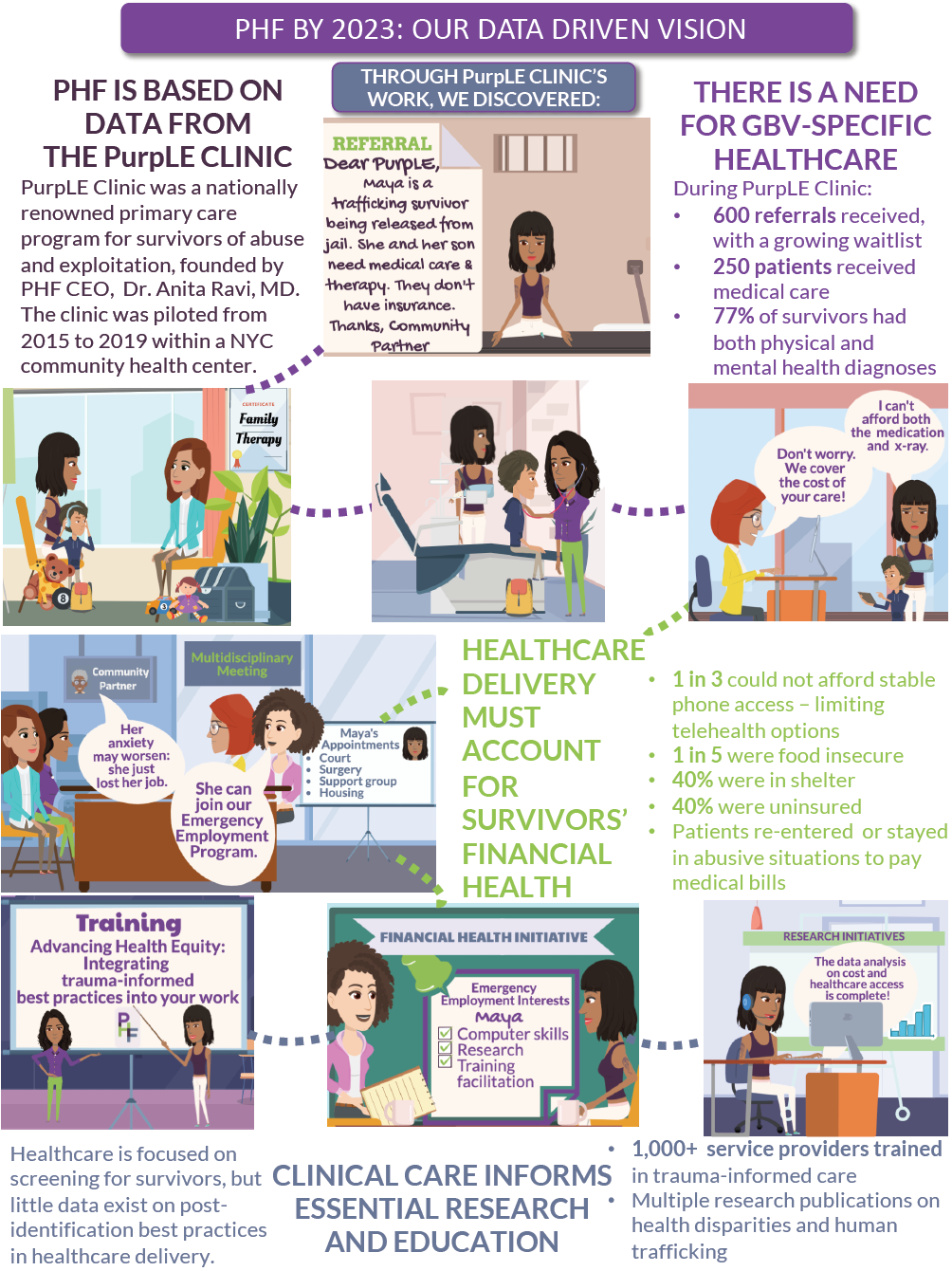

The atmosphere in the trailer would fluctuate between an emergency room (ER) and a pediatric ward: critical life and death issues were being managed, the need outnumbered the staff, time is low and the stakes were high. And at the same time the intermittent presence of the classic white-pink-blue American blanket, a staple in newborn nurseries would result in brief disorientation, and seeing their presence on an ID card to track them instead of on a birth certificate was even more disconcerting. Each time, I would remind myself that we were outside of a hospital and inside of a detention center.

I have always been aware and uncomfortable with the necessity of risking retraumtatization of victims in the process of helping secure their asylum. Repeating stories of trauma is inherently retraumatizing, and is often a large deterrent in survivors moving forward in the asylum process. Despite this, there are subtle signals that it is parental love that propels mothers through the acute and chronic trauma inflicted by their persecutors and the asylum-seeking process itself.

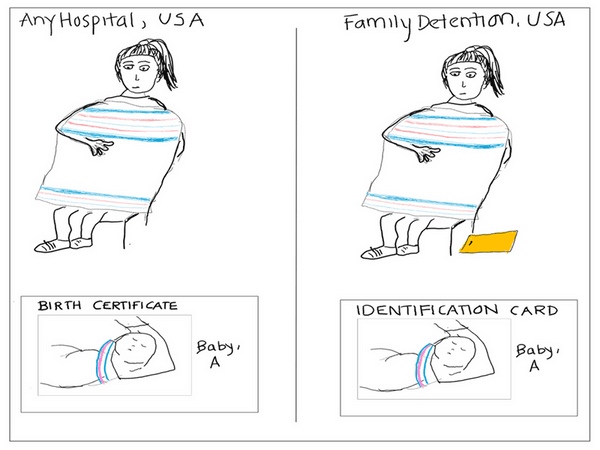

The structure of each day results in CFI preps every two hours. New groups of mothers and children, dressed in detention-issued uniforms of jeans, sneakers and solid color tops to identify the housing units they come from (not unlike prison) begin the process by sitting in a circle listening to "Know Your Rights" presentations. Sometimes the women are clutching their child in one hand and their manilla envelope containing all of their papers in the other. And in direct competition to their efforts to obtain this essential information is a soundtrack of childrens' coughs, cries, and a loud television blaring the voices of carefree, animated characters churning in the background.

Bordering the common space where the rights presentations occur are private meeting rooms where we met with clients to prepare for their Credible Fear Interview. Inside, mothers are asked to recount the traumas that led them to seek safety in the United States. And they typically do so while soothing screaming toddlers, coughing infants, and attempting to mask their own tears from their all-to-aware children, while also attempting to process the critical information needed as the clock ticks towards their interview time. It is a truly super-heroic effort to witness.

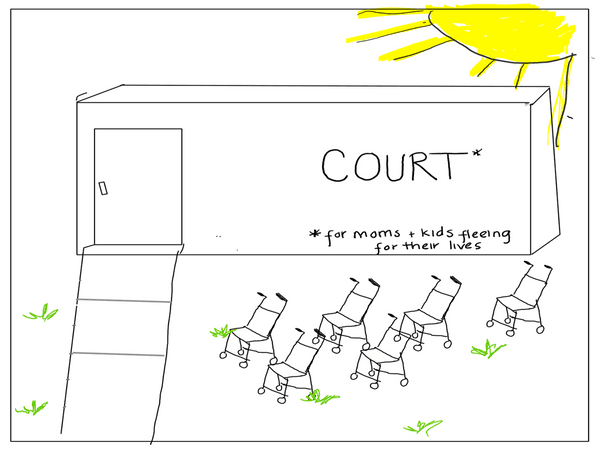

After CFI prep, mothers await their CFI. An informal parking lot of empty strollers are lined up outside of the court trailer, where the CFIs take place. Inside, the women (and sometimes their children), sit anxiously in a waiting room as they listen for their name to be called by the asylum officer. The atmosphere is thick with anxiety and attempted distractions. But each time an officer appears, the woman does a quick study of the officer's face. Will they be kind? Will they be patient? Everything hinges on what transpires in the next 90 minutes with this stranger.

For those mothers and children who are released from detention, it's difficult to fathom that this is only the beginning. Years of repeating their story to prove their credibility while combatting family homelessness, illness and hunger await them. But my week in Dilley also made me realize what an unfortunate privilege it is to work in a field where I need not refer to the women I meet as "aliens." Health is universal, and their immigration status does not determine my dedication to their care.

The Advocacy

My time in Dilley also made me reflect on my efforts as a physician advocate. Last year, I was part of a multidisciplinary immigration advocacy team which came together to end family detention and oppose the separation of parents from their children. Related resolutions were ultimately adopted at the AAFP's NCCL and the AMA House of Delegates. Since then, I have collaborated with lawyers who bring health concerns of their clients to our attention. When they began to notice a practice of detaining pregnant women, our Academy acted immediately, issuing a letter to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement outlining the health harms of detention of pregnant women.

But Dilley appears to be impenetrable to the causes we've advocated for on behalf of asylum-seeking mothers and children. The first CFI prep I assisted with was with a detained pregnant mother, and mothers still harbor the very real fear of separation from their children. Resolutions and statements are critical steps but clearly not enough. So how else can family physicians harness our critical expertise of understanding medicine, mental health and maternal-child health to improve the care of this hidden population? For now, our best chance may be to amplify the moments that bind us on our basic instincts across culture: fear, safety, resilience and love.