How Do You Deal With the Trauma? VT and Me

Have you heard about VT?

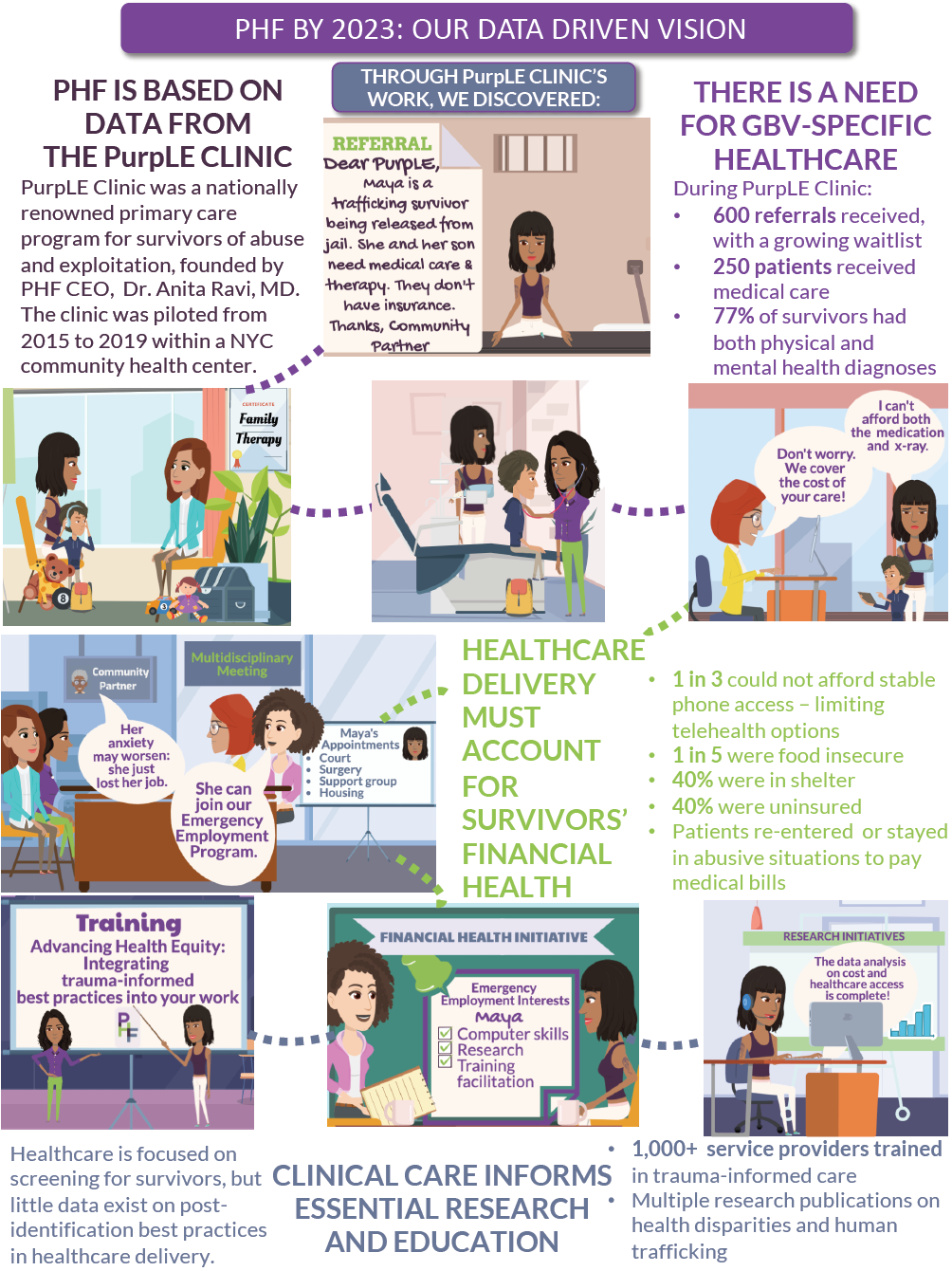

The first time I learned about it was in 2014 from a concerned human trafficking lawyer. I was in the beginning stages of forming what would go on to become the PurpLE Clinic -- a family medicine clinic for people who have experienced human trafficking, domestic violence and other forms of violence -- and was seeking her advice. Anticipating the repeated exposure to traumatic stories inherent in this work, she asked what I would be doing to address vicarious traumatization (VT).

"Oh, umm ... I guess I hadn't really thought about it," I said.

She was alarmed.

"No one has asked you how you'll take care of yourself?" she asked.

She shared how VT had crept up on her and told me I should watch out for it. I should be prepared.

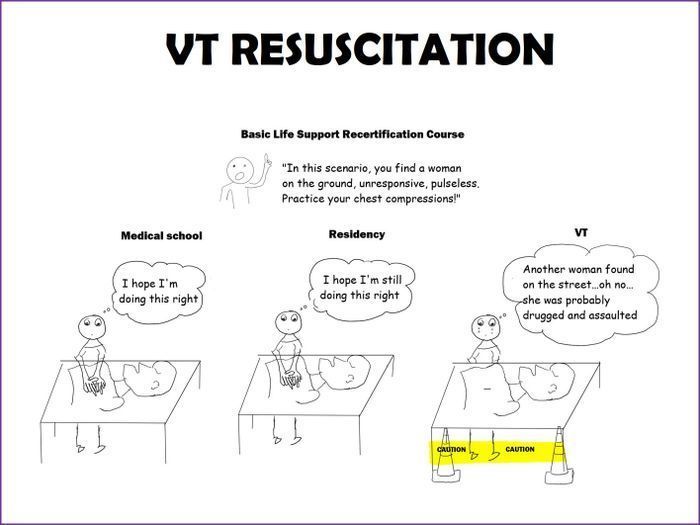

Vicarious traumatization, sometimes called secondary trauma, can develop among people whose jobs routinely expose them to trauma, including first responders, law enforcement, social workers, journalists and health care professionals. Being a physician inherently exposes us to this occupational hazard; we witness pain, losses and deaths steadily and mechanically as part of our indoctrination into the tribe of medicine. So, when the doors of my clinic opened one year later, I thought my training as a physician had adequately prepared me to address VT.

I was wrong.

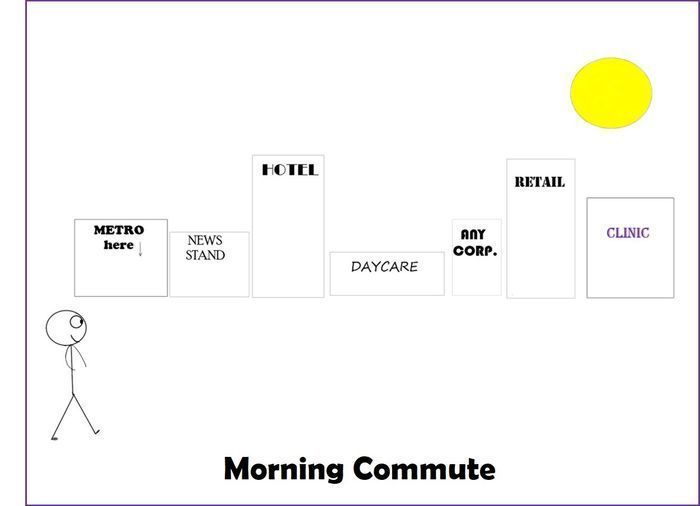

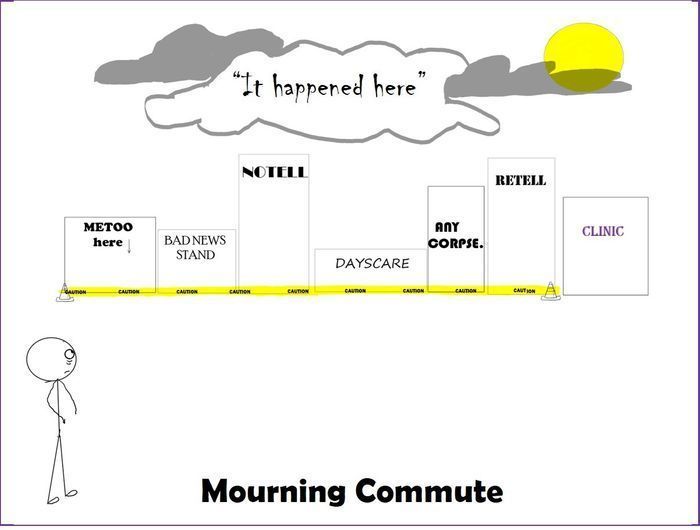

Medicine taught me ways to process the loss of life, but it did not prepare me to process the loss of safety in life. Meeting patient after patient who was harmed by someone known to them, unknown to them, in homes, in schools, in alleyways and police precincts, as children, as adults, once or repeatedly, expectedly or unexpectedly, shook the structures of security around me. Settings I had previously deemed innocuous -- elevators, parks and salons -- were now recategorized in my brain as crime scenes. I could not unsee dangers that lurked everywhere. I had not yet learned that VT can include "changes in one's safety in the world."

I also hadn't learned how VT would present itself. I thought it was the same as burnout or "caregiver fatigue." I thought it would mean crying or feeling sad after a challenging patient encounter. Armed with this misguided belief, I vigilantly tracked my post-visit reactions. And when I found myself feeling happy to meet new patients and relief at the end of each clinic because, despite their encounters with profound and disruptive violence, people were able to come in and connect with health care, I would make a mental note to myself of having successfully dodged VT for that day. Phew!

But then, inexplicably, 48 hours later, while ordering coffee at a bakery, flashes of conversations from clinic would begin to replay, and as I slowly recognized the gravity of the situation I had heard, I would find myself tearful, despondent and dejected. All of a sudden, a routine coffee pick-up would turn into a slowed, measured, painful interaction with the world. The reason it was inexplicable was that I had not yet learned that VT happens over time and can include disruptions in thinking.

VT crept up in other unexpected ways. It crept up during my CPR recertification course, when instead of performing chest compressions on the mannequin, I stood in front of the unresponsive plastic body, vacantly tearful. It crept up in the middle of the night as sweats from clinic-related nightmares, and in the middle of clinic as a scream when a nurse would unexpectedly knock on the door and my hypervigilance got the best of me.

And it crept up every time I would try to close a patient's chart.

As in many health care systems, those in our organization who had incomplete charts for more than 48 hours were added to a list that would be sent out practice-wide. I would do everything I could to avoid finding myself on this list. But as the months passed, I began to accept the shame in seeing my name. It was hard for me to understand my aversion to returning to the chart and formally closing it. Logically, I just had to type out what was discussed at the encounter, click some buttons and sign the chart. But emotionally, 48 hours was not enough. When a patient left, I didn't want to return to the chart. I didn't want to look at it. I felt a hot burden of wanting to do right by my patient's story in the documentation, but my fingers and brain rebelled against typing out the details of the ways in which my patient had been hurt. To type it was to acknowledge another way that violence existed in a darkening world.

Later, with great relief, I learned that a social work colleague who also worked with trafficking survivors faced a similar challenge at her organization -- documenting the traumas of her clients was a daily mountain awaiting either conquering or disciplinary action. It became clear that in our shared universe, unclosed charts were not a display of irresponsibility, they were a symptom of vicarious traumatization.

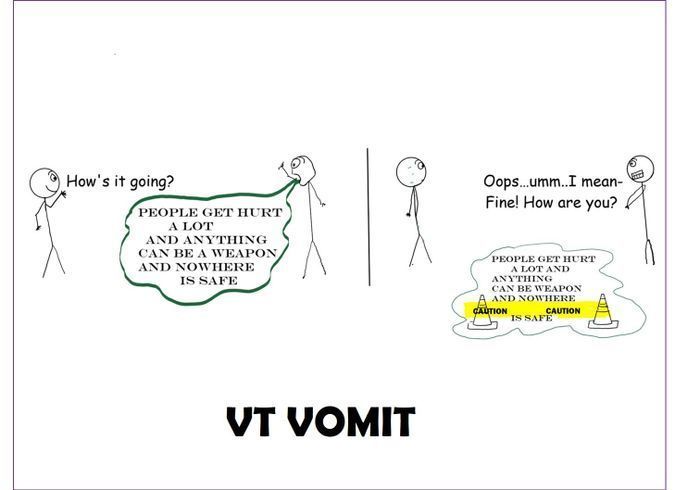

So, what did I do about this? I began to stitch myself a safety net. It was hard for family members, colleagues and even coffee shop baristas who would innocently ask, "How's it going?" to find themselves covered in my VT word vomit -- lamenting my frustrations with broken systems and haunting them with the promise that the world isn't as safe as they think it is. My traumatization had become irresponsibly infectious; by not having a way for me to process it, I was unintentionally putting others at risk to absorb it, whether they were ready or not. Having my therapist, a dedicated person trained to listen to my worries and reflections on medicine and beyond, became an essential knot in my safety net.

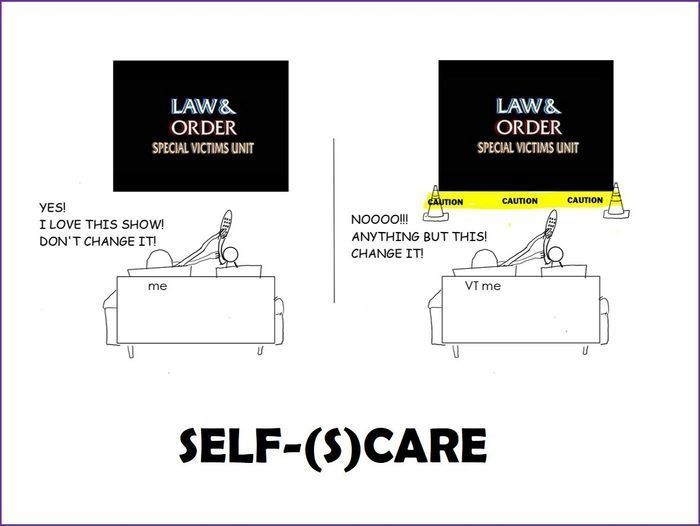

I also sought support and advice from my colleagues outside of medicine. Comprehensive care for people who have experienced sexual trauma means multidisciplinary care, and I was fortunate to find myself in this new tribe of social workers, therapists and lawyers from partner organizations, all of whom are deeply invested in our shared patients/clients. These colleagues stepped up when I revealed my increasing perception of a cold, gray world around me. They invited me to debrief with them and shared their self-preservation practices. ("I can't watch Law & Order: Special Victims Unit" is a common sentiment in our VT world.) They discussed their teams' best practices of routine check-ins, strategically structured visits that optimize client care while minimizing VT, and commitment to setting aside sacred, uninterruptible times for processing cases with their larger teams -- rituals that are largely foreign in the culture of medicine.

Support also came in the form of larger institutions, such as the Office of Victims of Crime, which developed a vicarious trauma toolkit to support teams that are chronically exposed to trauma. These elements were also woven into my safety net.

So why am I sharing this? I am sharing this because I feel an intense responsibility to proactively alert students, residents, research assistants and anyone else joining our team about the ways in which their world will change -- perceptibly and imperceptibly -- when engaging in this work, just as the human trafficking lawyer kindly did for me when I first started.

I am sharing this so other physicians who may be suffocating from unclosed charts and surprised by delayed reactions to difficult stories can feel supported in constructing their safety net.

I am sharing this because "How do you deal with the trauma?" is the most common question I receive after any presentation I give about PurpLE Clinic, and it needs an honest response.

And I am sharing this because when my patients respectfully inquire, "Can you handle my story?" I want them to know why and how my answer is truthfully grounded in "Yes."